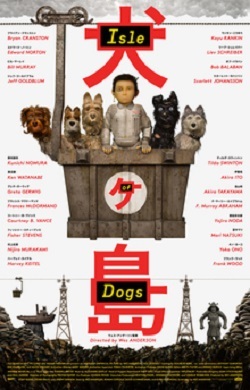

Isle of Dogs: Offbeat, In More Ways Than One

Isle of Dogs is in so many ways a quintessential Wes Anderson movie. It is beautifully filmed, the characters–even though they are dogs–are believably quirky yet still slightly exaggerated, and playful, dreamlike storytelling mingles seamlessly with blunt and ugly truths. And yet despite all the charm and genuine sentiment Anderson imbues Isle of Dogs with, there is a flaw at its center which makes it a weaker film than it should be.

The story begins when Mayor Kobayashi, a scheming Japanese politician, has all the dogs in his city banned to an island used as a garbage dump–he intends to kill them after he steals an election. Kobayashi’s twelve-year-old nephew Atari flies a small plane to the island in search of his own dog, Spots, and becomes involved helping all the abandoned dogs manage their own rescue. A group of students lead the resistance against Kobayashi in the city.

Anderson as always assembles a familiar and stellar cast. Bryan Cranston, Edward Norton, Bob Balaban, Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum, Scarlett Johansson, Harvey Keitel, Tilda Swinton, F. Murray Abraham, Fisher Stevens, Anjelica Huston, and Liev Schreiber all lend their considerable talents to voicing the many dogs. The human characters are portrayed by Greta Gerwig, Frances McDormand, Courtney B. Vance, Frank Wood, Koyu Rankin, Kunichi Nomura, Akira Takayama, and Yojiro Noda. Yoko Ono and Ken Watanabe have small, almost stunt parts.

The movie has the flavor of the 1950’s vision of the near future, with a dash of postapocalypse thrown in. There is strong and pointed political commentary. There is a hint of Godzilla and James Bond in the bad guys and their over-the-top mechanical weapons. The artwork and puppetry are amazing, detailed and convincing and realistic. The dogs are beautifully rendered, from their eyes to their dirty fur to their scars. The backgrounds glow. The story is heartwarming without being sentimental, with authentic emotional development and honest consequences. Isle of Dogs has the potential to become a classic.

And yet.

There are missteps which I believe keep Isle of Dogs from being as fully wonderful as it should be. For one, I found the names distracting: Kobayashi, Atari, Major Domo, and Yoko Ono are all so obvious as to be dismissive. For another, the use of tired character clichés like the schoolboy hacker undercut the strength of the storytelling. But Anderson’s biggest mistake is that he inserts a transfer student from Cleveland, Ohio into the middle of his story’s Japanese political battle, and makes her the spokesman and heroine of the resistance. She is blonde, loud, and brash; if this was meant as a knowing wink toward the trope of the white savior, it missed its mark by a hemisphere. If the character was in earnest, the tone-deafness is uncomfortable to witness. While Anderson has been accused of cultural appropriation, what comes across to me is more a lazy attempt at cleverness that falls short of its intended effect.

As a long-time fan of Anderson’s work, I truly enjoyed all the familiar, oddball personalities and the reliable charm he brings to his storytelling. Despite its problems, Isle of Dogs is a lovely, touching movie. But I hesitate to call it one of his best.