Read This: The New Annotated H.P.Lovecraft

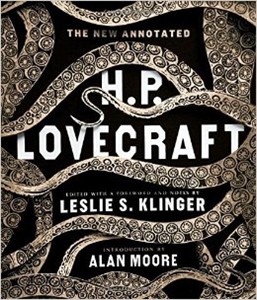

The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft. By H.P. Lovecraft, Edited with a Foreword and Notes by Leslie S. Klinger, Introduction by Alan Moore. New York, NY: Liveright; 13 October 2014; ISBN 978-0-87140-453-4; 922 pages; hardcover.

The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft. By H.P. Lovecraft, Edited with a Foreword and Notes by Leslie S. Klinger, Introduction by Alan Moore. New York, NY: Liveright; 13 October 2014; ISBN 978-0-87140-453-4; 922 pages; hardcover.

The thing about Lovecraft (or about any iconic writer, really), is that you get used to the pastiches, the tributes, the imitations and derivations. It is a necessity, then, to return to the source at intervals and remind yourself exactly why this author has inspired so many people over so many years to try to tap into the rich, dark, cryptic world he created.

Sometimes it seems as if every writer banging away out there has tapped into the shadowy world Lovecraft seeded for us. Sometimes it feels a little cheap, as if we should come up with our own monsters. But in The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, Leslie S. Klinger makes Lovecraft’s intentions about the use of his ideas abundantly clear: “The more these synthetic demons are mutually written up by different authors, the better they become as general background material. I like to have others use my Azathoths and Nyarlathoteps–& in return I shall use Klarkash-Ton’s Tsathoggua, your monk Clithanus, & Howard’s Bran” (lxiii).

The book itself encourages that sharing. It makes a reader want to pick it up, feel it, and weigh what might be inside. The first thing to notice about it is that it is a truly handsome edition, with heavy pages and a cover laced with tentacles. Physically, it is a striking representation of its content. Lovecraft is dense and dark. This book is, too, with the ivory paper mimicking aged parchment and lending a sepia tint to the illustrations. The blurbs are from a selection of heavy-hitters in the field of weird fiction such as Neil Gaiman, Harlan Ellison, Peter Straub, and Joyce Carol Oates (as much as I find Oates’s novels draining, her short, macabre pieces are chilling).

Rather than taking on the entirety of Lovecraft’s work (which has been done before and often), Klinger instead looks closely at twenty-two stories and novels. This volume covers the instantly recognizable titles like The Call of Cthulhu and The Shadow Over Innsmouth to the less immediately known but still resonant The Festival and The Silver Key.

The annotations are thorough, and liberally sprinkled through with original magazine covers and illustrations, examples of handwritten drafts, and photographs of many of the places referenced in the stories. Klinger does a remarkable job of recreating the environment in which Lovecraft worked, showing his readers the prosaic structures and neighborhoods that Lovecraft twisted into his own world.

The appendices are a treasure. Appendix 1 is a chronological table of events in Lovecraft’s works, beginning with the 1771 death of Joseph Curwen in The Case of Charles Dexter Ward to the 1935 storm over Providence in “The Haunter of the Dark”. Appendix 2 is a partial list of the faculty of Miskatonic University, including each one’s position and the story in which he appeared. Three is Lovecraft’s own outlined history of the Necronomicon, itself footnoted by Klinger and including a reproduction of Lovecraft’s original version written on and around a letter he received from the director of the Park Museum in Providence. Four is the genealogy of the Elder Races as laid out by their creator, five a list of Lovecraft’s solo fiction output with dates of writing and publication, again with a reproduction of Lovecraft’s own handwritten list, and six a list of his collaborations (whether openly or as ghostwriter), which include such figures as C.L. Moore, Robert E. Howard, and Harry Houdini. Appendix seven is a compact overview of Lovecraft’s influence in popular culture that focuses primarily on the films he inspired.

The appendices bring us to the end of the physical book, but the beginning is really where the challenge still waits. Alan Moore’s introduction foreshadows the literary criticisms that will follow in the foreword and annotations, honing in on the substantial baggage Lovecraft carries with him across the decades. He describes the struggle to create a literary legitimacy for Lovecraft’s works after his death, a task that “…has undeniably been hindered by his problematic stance on most contemporary issues, with his racism, alleged misogyny, class prejudice, dislike of homosexuality, and anti-Semitism needing to be both acknowledged and addressed before a serious appraisal of his work could be commenced” (xi). Moore himself is dealing with it in his own way, through a gay, Jewish character in his series Providence. And he still describes the interest in and appreciation of Lovecraft’s craft as a “posthumous trajectory from pulp to academia that is perhaps unique in modern letters” (xi).

Klinger’s foreword provides a brief biographical summary that also does not shy away from the increasingly inevitable, uncomfortable topic of Lovecraft’s racism and how it manifested in his actual life and as part of his tangled cosmology:

Although his attitudes may be dismissed as products of the times, his words do not display casual racism…It seems that Lovecraft’s peculiar upbringing, combined with his family’s tenuous social position in Rhode Island society, grafted onto his consciousness a hostility to virtually all who were not white New Englanders…Although the times changed, and the “scientific” bases for racism and eugenics that he embraced eroded over his lifetime, Lovecraft remained static and unbending. Worst of all, his beliefs may be seen as essential to several of his stories, such as “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” which imagines the horror of interspecies breeding (lxvi).

Unfortunately, the flaws in Lovecraft’s morality set up questions for the morality of his modern readers. Are we justified in enjoying his works, revering them, even though we know that the author held some execrable beliefs that informed some of his best-known and most admired work? Is it acceptable to separate an artist from his art, and treat the creator and the creation as two independent entities?

Moore, in his introduction, felt that the art transcended the man. Not all would agree, but we read on, just the same.