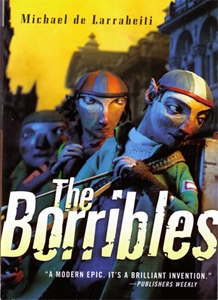

Read This: The Borribles

The Borribles, Michael de Larrabeiti’s cleverly subversive young adult fantasy novel, was first published in 1976. Since then, it and its sequels have drifted in and out of print, with the most recent reissue coming in 2014 from Tor Books. So why, exactly, would I recommend a fortyish year old British children’s book to a group of modern gamers?

The intellectualized answer is that it is a classic hero’s journey as described by Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces and as recently explored in our own Gail Brooke’s article “The Apotheosis of Journey.” It is a grand adventure the likes of which all our alternate selves aspire to. It is impossible not to recognize: an unlikely group assembles to battle a fearsome foe, and along the way they bond, change, and grow before they return from whence they came.

The real answer, though? I loved this book as a twelve year-old, and I love it as an adult. I have read it probably a dozen times across the years, and keep my hardcover copy on my “special” bookshelf. Like all great stories that bridge that age-gap, its engaging surface flows over more complicated themes and the story it tells can be enjoyed and interpreted on multiple levels.

De Larrabeiti’s novel follows eight (mostly) unnamed Borribles, who are selected to go on a grand campaign to rid London of the scourge of the acquisitive, competing Rumbles. Rumbles are like large, soft rats, and hate the Borribles as much as the Borribles hate them. The eight are charged with invading the underground stronghold of Rumbledom and eliminating the Rumbles’ High Command. The entire endeavor is extremely un-Borrible-like (Organization! Training! Rank!), but the desire to be part of an adventure of this magnitude is irresistible to the eight hearty souls who set out for glory.

For the younger set, it can easily be read as the slightly naughty story of an epic quest by a bunch of rather naughty creatures. Borribles, after all, are the best kind of naughty—capable, smart, and not accountable to adults for anything they want to do. As de Larrabeiti describes them:

“Borribles are generally skinny and have pointed ears which give them a slightly satanic appearance. They are pretty tough-looking and always scruffy, with their arses hanging out of their trousers, but apart from that they look just like normal children, although some of them have been Borribles for years and years… They are proud of their quickness of wit. In fact it is impossible to be dull and a Borrible because a Borrible is bright by definition” (12).

The fact that the less polite bits are couched in British slang adds a certain romantic quality on this side of the wide Atlantic.

While they are in many ways strange, fey urchins, de Larrabeiti’s Borribles are still not supernatural: “Normal kids are turned into Borribles very slowly, almost without being aware of it; but one day they wake up and there it is. It doesn’t matter where they come from as long as they have what is called a “bad start”. ” (12). They have adapted to an environment that is not well suited to human children, and have exploited it with great efficiency.

Borribles survive by squatting in empty buildings and pilfering whatever they can, and tend to avoid the police by hiding in plain sight. They masquerade as still-human children by keeping woolen hats pulled down over their pointy ears. In fact, they can be forcibly reverted to human children if the police do get hold of them. It makes perfect sense that their primary guiding principle is, “Don’t get caught.”

If they do get caught, their ears are clipped and they resume their previous human condition. This is never a happy ending. De Larrabeiti’s creepiest villain (among many) in the book is the old rag-and-bones man Dewdrop, an embittered former Borrible turned dreaded Borrible-catcher: “I’m a good friend to the Borribles, always have been. They help me and I help them. Was one myself once, ain’t it, till I got caught. Nasty business growing old. You don’t ever want to get caught, do you?” (109).

That particular threat hangs over the heroic Borribles throughout the entire book, and amidst the action and adventure are episodes of real darkness. Our Borribles make mistakes they can’t walk back, they betray and are betrayed, they lose what they care about and they sacrifice themselves. As a child, I (and I’m sure, most others) accepted all these events as merely sad parts to the story without looking for more. Now, the older set can read into it what they will: a musing on mortality, or responsibility, the loss of innocence, or the inescapable fact that everything changes and all good things must eventually end.

Or not. As I said at the top, there are multiple layers to this story, from childlike bravado to adult nostalgia. Find your level. Keep your hat on, keep your ears covered, and dig in.

E.A. Ruppert contributes book and media reviews for NerdGoblin.com. Thanks for checking this one out. To keep up with the latest NerdGoblin developments, please like us on Facebook , follow us on Twitter and Pinterest, and sign up for the NerdGoblin Newsletter.

And as always, please share your thoughts and opinions in the comments section!